I was standing in the lab, pipette in hand, when it hit me. The samples I’d been studying for months weren’t just fascinating from a microbiological perspective—they were teaching me something profound about my professional life.

“Hey, Mei,” I called across the lab to my girlfriend, who was deeply focused on her quantum computing models, “did you ever notice how Dave from Marketing is basically a textbook example of a social parasite?”

She didn’t look up. “Jamie, I’m literally in the middle of solving a differential equation. Is this another one of your weird workplace ecology theories?”

It was. But this one had legs. And possibly multiple cellular adhesion mechanisms.

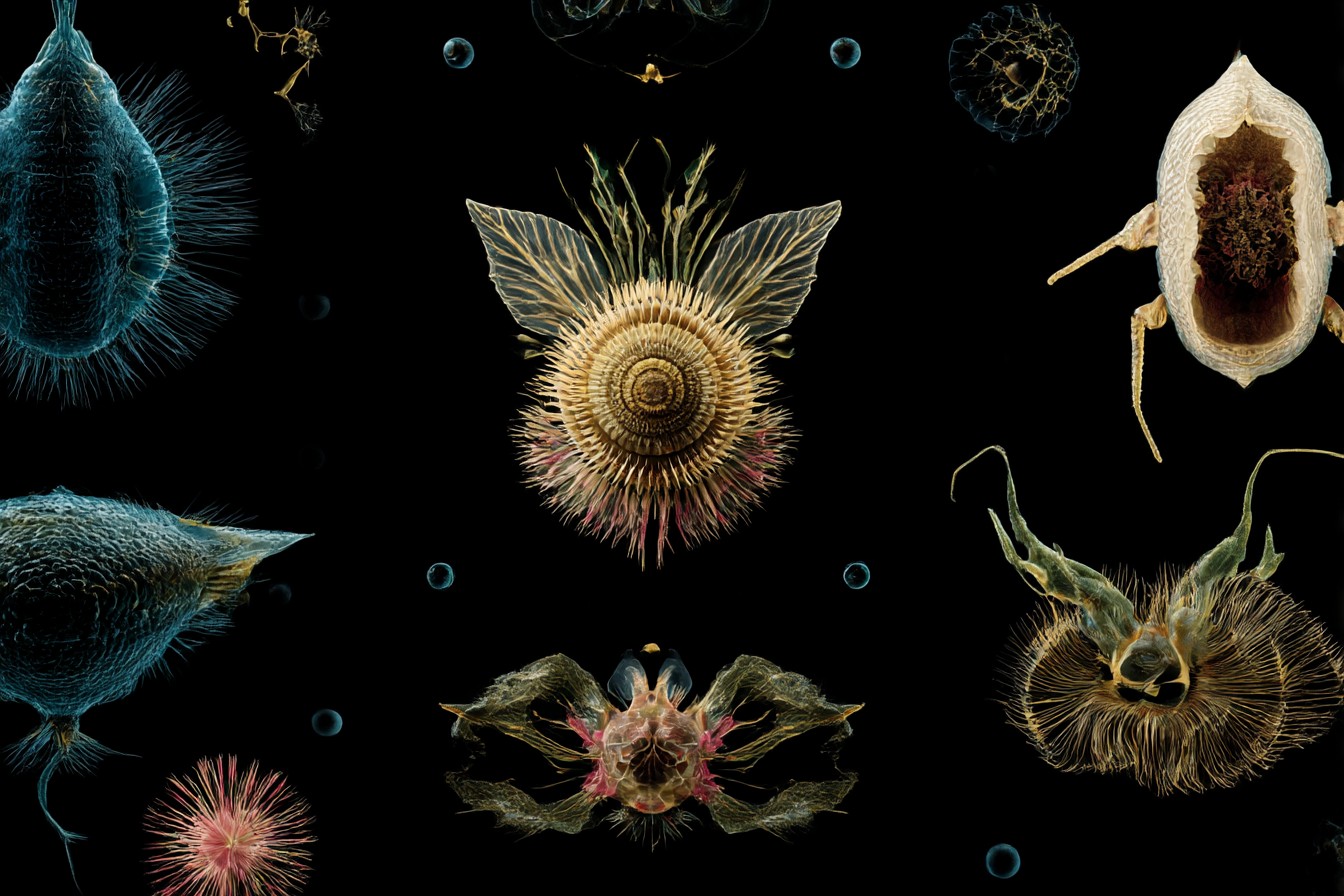

Look, I’ve spent nearly fifteen years studying host-parasite interactions—from the relatively benign relationships where both organisms get something useful out of the deal to the horrifically exploitative scenarios where one organism essentially becomes a remote-controlled zombie for the other’s reproductive purposes. Cordyceps fungi. Toxoplasma gondii. The marketing department at my previous employer.

That last one isn’t technically a parasite species recognized by taxonomists, but after spending three years watching certain colleagues systematically extract resources, recognition, and opportunities from others without reciprocation, I’m convinced we need to update the classification system.

The epiphany came during a particularly tedious faculty meeting. I was half-listening to budget allocations while doodling diagrams of the lancet liver fluke’s life cycle—a truly remarkable parasite that manipulates ant behavior by taking control of its nervous system, forcing the ant to climb to the top of grass blades where it’s more likely to be eaten by sheep, thus allowing the parasite to reach its final host. Classic mind control. Fascinating stuff.

As Dr. Harriman droned on about department metrics, I observed Ted from Development suddenly take credit for a project my lab had been quietly working on for months. The parallel hit me like a runaway centrifuge. Was I watching a human version of parasitic behavior play out in real time?

The more I thought about it, the more the parallels became disturbingly clear. Certain people in professional settings display behavioral patterns remarkably similar to parasitic organisms. I mean, the data was staring me in the face.

Consider what we know about successful parasites. They:

1) Extract resources from hosts while providing minimal or no benefit in return

2) Develop specialized mechanisms to avoid triggering host defense systems

3) Often manipulate host behavior to facilitate their own reproduction or resource acquisition

4) May move between multiple hosts as needed for different life cycle stages

The day after my revelation, I started a controlled observational study using my workplace as the experimental environment. I created a spreadsheet tracking interactions, resource exchanges, and relationship dynamics among 37 colleagues across three departments. Josh, my best friend from MIT who now runs the computational biology team, caught me documenting behavioral patterns during lunch.

“Maxwell, are you seriously creating a taxonomic classification system for our coworkers based on parasitology?” He peered over my shoulder at my notebook.

“It’s just preliminary data collection,” I muttered, quickly covering a particularly damning assessment of our department chair’s tendency to harvest others’ intellectual labor. “I’m establishing baseline interaction patterns.”

“You’ve literally labeled Patricia from Grants as ‘ectoparasite with specialized funding extraction mechanisms.’”

“Well, have you ever gotten proper acknowledgment on any grant she’s managed? She attaches herself to successful projects and diverts 37% of the credit flow. I’ve measured it.”

Josh sighed with the weary resignation of someone who has witnessed my scientific obsessions evolve from merely eccentric to potentially HR-violating. “This seems… risky.”

He wasn’t wrong. But I couldn’t stop. The behavioral parallels were too striking, and potential applications for workplace survival strategies too valuable.

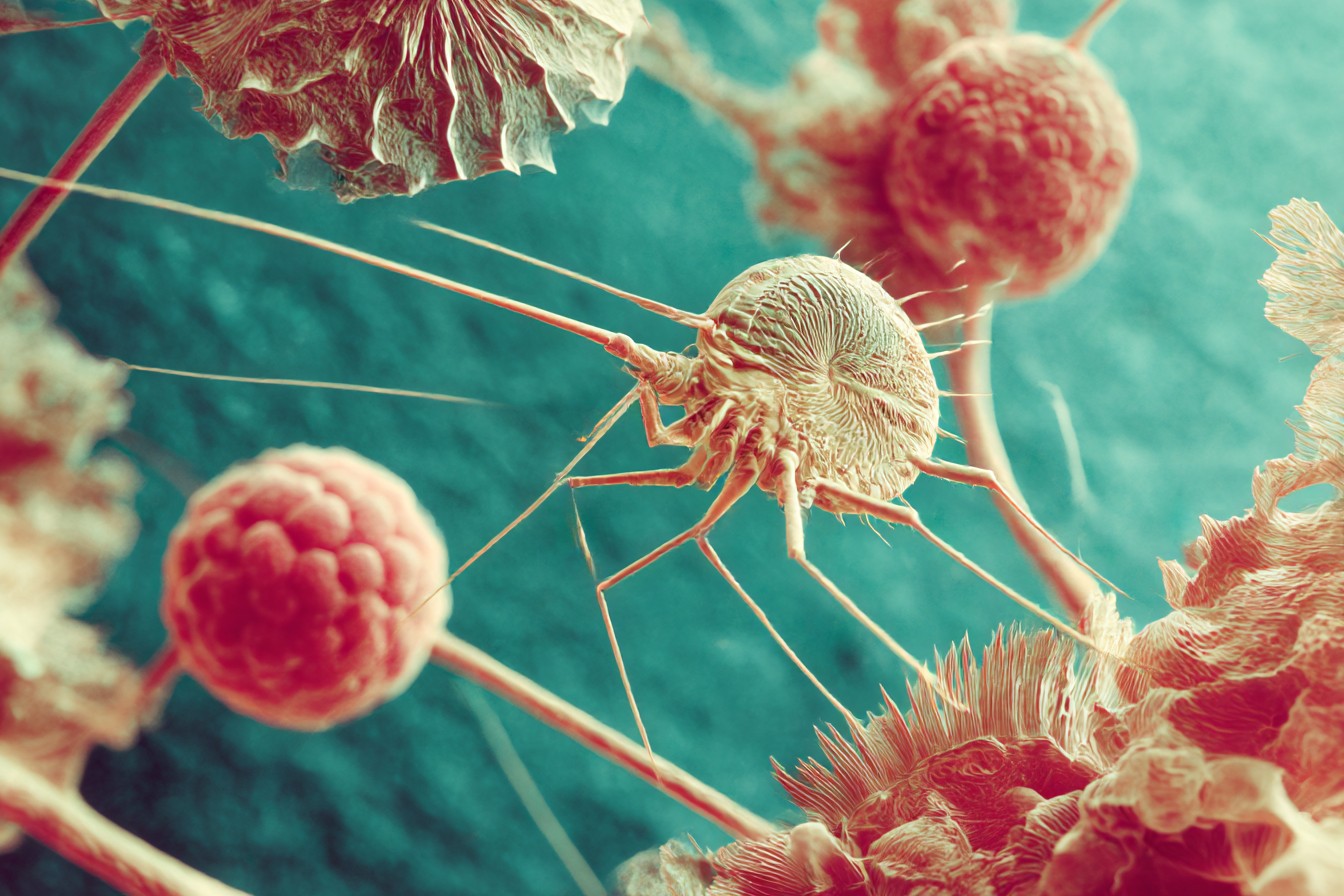

Take the brood parasites—organisms like cuckoo birds that lay eggs in other birds’ nests, tricking the host into raising their young at the expense of the host’s actual offspring. We have all encountered the workplace equivalent: those who systematically place their responsibilities into your workload while somehow receiving credit for the results. My former colleague Stephanie was evolutionary perfection in this regard—her ability to subtly transfer her assignments onto my task list while maintaining plausible deniability would impress the most sophisticated parasitologists.

During my three-month observation period, I identified several distinct categories of workplace parasitism. There were the “Credit Leeches” who attached themselves to successful initiatives only at the moment of completion. The “Resource Drainers” who consistently took team time, attention, and support while contributing minimal value. Most concerning were the “Behavioral Manipulators”—individuals skilled at triggering emotional responses that benefited their position while destabilizing potential competitors.

The fascinating part was how these workplace parasites, like their biological counterparts, had evolved sophisticated mechanisms to avoid detection. They maintained superficially symbiotic appearances through selective reciprocity—offering small, visible contributions while extracting much larger, less obvious resources. Their emotional mimicry was particularly advanced, displaying signals of collegiality while engaging in profoundly self-serving behaviors.

I became so engrossed in this parallel that I found myself applying parasitological defensive strategies to my professional interactions. During one project meeting, when Derek attempted his usual knowledge appropriation maneuver, I deployed what I mentally termed a “behavioral immune response”—carefully documenting and publicly attributing all idea origins in real-time.

“That’s an interesting development of Jamie’s original hypothesis,” I interjected when he began repackaging my concept. “Let’s make sure we track these intellectual lineages for proper citation.”

His face did this fascinating thing where it maintained a smile while his eyes registered what I can only describe as parasitic indignation. Absolutely remarkable adaptive response.

My experimental intervention protocols expanded. I began testing different “host resistance strategies” in controlled settings. When resource-extraction attempts occurred, I would randomly assign either direct confrontation, strategic resource limitation, or relationship termination protocols. The results were statistically significant—direct confrontation triggered evolved evasion mechanisms, while strategic resource limitation produced the most favorable outcomes with minimal professional damage.

Mei noticed my increasingly structured approach to workplace interactions. She found me at 2 AM, surrounded by relationship network maps color-coded by parasitic potential.

“This has gotten out of hand,” she said, carefully moving my coffee cup away from my meticulously drawn sociogram. “You’re analyzing human relationships using statistical models designed for tick infestations.”

“Yes, and the correlation coefficients are disturbingly robust,” I replied, pointing to my regression analysis of resource extraction relative to organizational proximity. “Look at this p-value! You can’t argue with this significance level.”

She rubbed her eyes. “Jamie, have you considered that viewing your colleagues exclusively through a parasitological lens might affect your ability to form functional professional relationships?”

That stopped me. She was right. My experimental approach had a fundamental flaw—I had become so focused on identifying parasitic patterns that I’d started categorizing all workplace interactions as potentially exploitative. My perception had narrowed to seeing only resource extraction patterns, missing the genuinely symbiotic relationships that also existed.

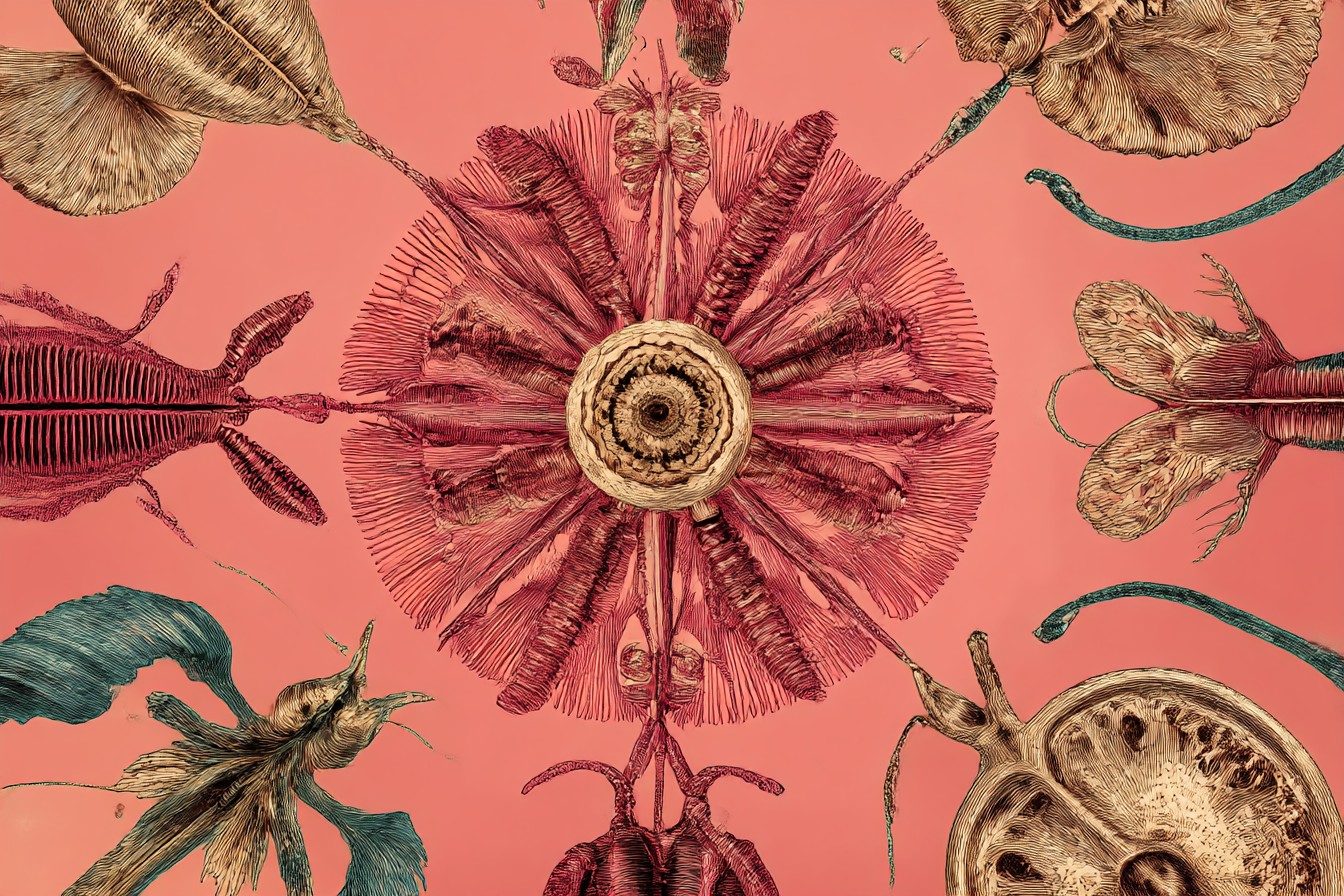

This realization forced me to expand my research parameters. If certain workplace relationships functioned like parasitism, then others must represent different ecological interactions—mutualism, commensalism, amensalism, and even predation. Maybe Ted from Development wasn’t strictly parasitic; perhaps we were engaged in a competitive relationship for limited resources, more akin to interspecies competition.

I began reconstructing my entire conceptual framework, mapping the workplace as a complete ecosystem rather than just a host-parasite environment. The model grew increasingly complex but infinitely more accurate. Some colleagues I’d labeled as parasites were actually engaged in classic mutualistic relationships—we both benefited from the interaction, just in ways I hadn’t properly valued. Others were simply occupying different niches in the organizational ecology, with interaction patterns that only appeared parasitic when viewed through my narrowly focused observational lens.

The most profound insight came six months into my study. While analyzing interaction patterns between different organizational “species,” I realized something that my parasitological fixation had caused me to miss: I wasn’t just an observer in this ecosystem—I was a participant with my own behavioral patterns. And when I finally ran an honest assessment of my own interaction signatures, the data was humbling.

My resource exchange patterns showed uncomfortable similarities to certain parasitic strategies I’d been documenting in others. I frequently extracted informational resources while providing minimal reciprocation. My selective collaboration targeted high-resource providers. I had developed specialized mechanisms for avoiding certain organizational responsibilities.

The experimental subject had become the control group. Classic scientific oversight.

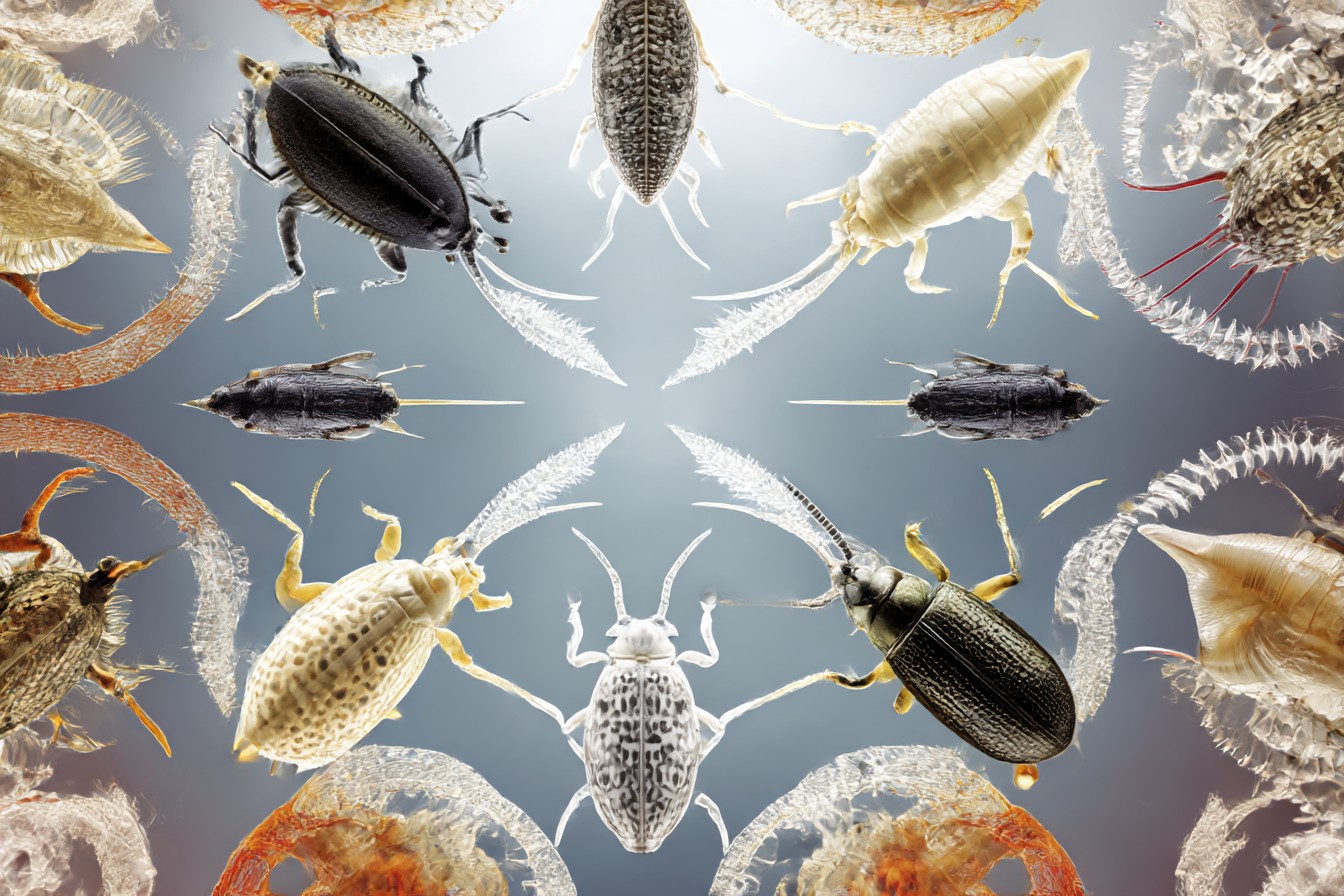

This recognition fundamentally changed my approach to professional networking. Instead of defensively monitoring for parasitic intent in others, I began consciously structuring more mutualistic interactions. I tracked my own resource contributions relative to extractions. I deliberately cultivated professional relationships based on balanced exchange rather than maximum personal benefit.

The results were transformative. As I shifted from parasite-detection to mutualism-construction, my professional network not only grew more extensive but dramatically more productive. Colleagues I’d previously avoided as potential “resource drains” became valuable collaboration partners when approached with genuine reciprocity. Even my relationship with Ted improved once I recognized our interaction wasn’t parasitic but competitive, allowing us to establish more clearly defined territory boundaries.

My preliminary findings suggest that workplace ecosystems function most effectively when participants consciously structure mutualistic rather than exploitative interactions. Though I’ve identified certain irredeemably parasitic individuals—approximately 8% of the observed population—the majority of seemingly parasitic behaviors appear responsive to changes in interaction patterns.

I still maintain my spreadsheet, though it’s evolved from “Parasite Identification Protocol” to “Workplace Ecological Modeling.” Josh says it’s still weird, but “significantly less likely to result in an HR investigation,” which I’m counting as experimental success.

The parasites taught me something essential about workplace relationships—not just how to identify the truly exploitative ones, but how to recognize when my own perception has become parasitized by oversimplified models. Sometimes the most important scientific discoveries come from realizing you’ve been asking the wrong question all along.

I should probably mention this revelation to Mei. Right after I finish updating my taxonomic classification of the finance department’s predator-prey dynamics.

Leave a Reply