It started with an itch, really. Not the metaphorical itch of scientific curiosity—though that certainly followed—but an actual, physical irritation three weeks into my decision to stop shaving. Mei had been visiting her parents in Seattle, and I’d embraced what Josh calls my “control group regression” (the tendency for my personal hygiene experiments to flourish whenever accountability leaves town).

Standing in front of the bathroom mirror, scratching absently at my increasingly substantial facial hair, I noticed something unusual—a tiny, almost imperceptible movement. I froze. There it was again. I leaned closer, my nose nearly touching the glass, and that’s when the thought hit me: What if my beard wasn’t just hair, but an ecosystem?

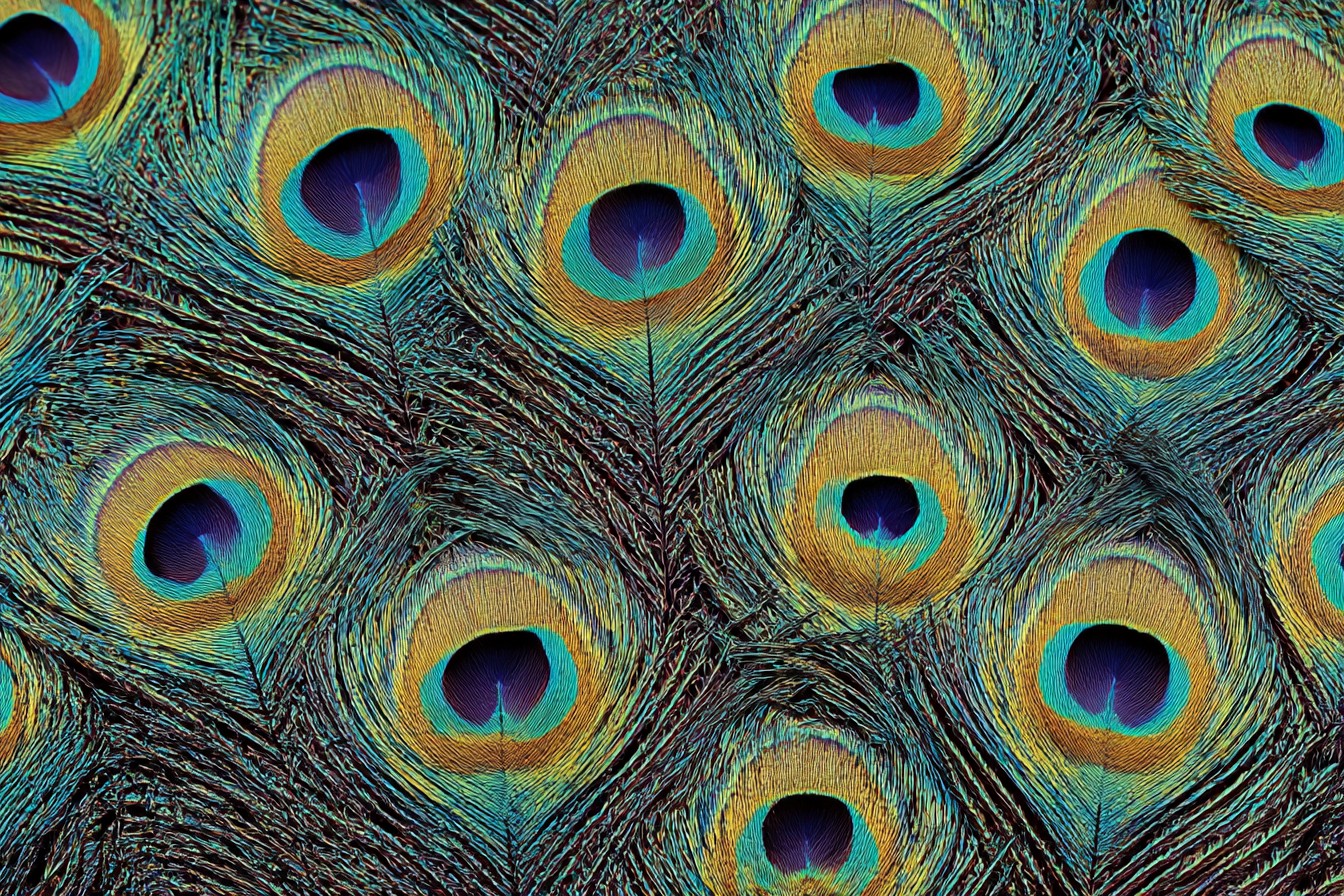

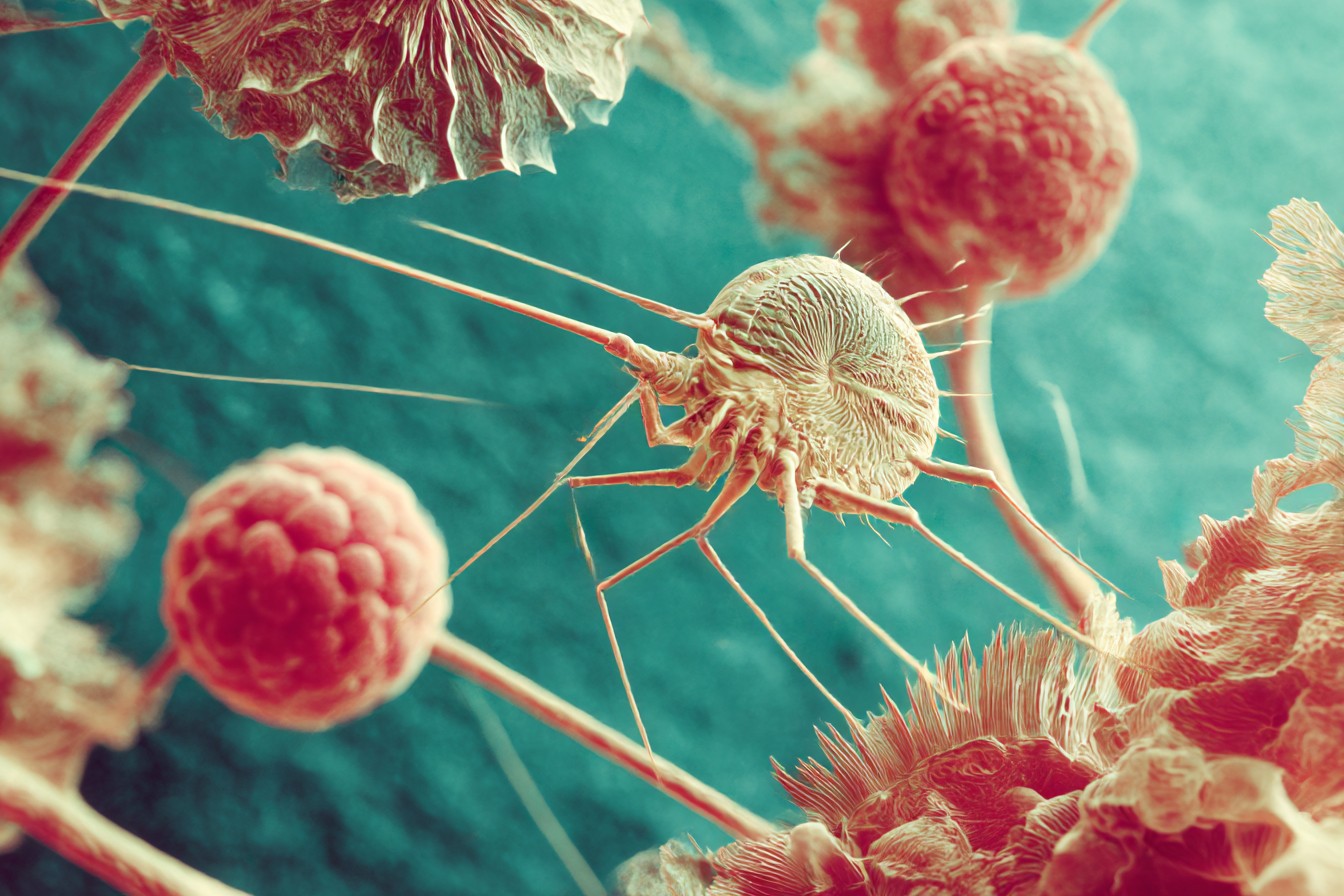

Look, I understand how this sounds. But consider the facts: the human face hosts thousands of microscopic mites (Demodex folliculorum, if we’re being specific) that live in hair follicles. We’re basically walking apartment complexes for countless microorganisms. My beard—now approaching what could generously be described as “nineteenth-century naturalist” proportions—potentially represented a massive expansion of habitable real estate.

The question formed itself: What exactly is living in there?

I immediately commandeered our bathroom, much to Mei’s dismay when she returned the following day. “I thought we agreed the bathroom was a science-free zone after the shower drain microbiome investigation,” she sighed, eyeing the microscope I’d balanced precariously on the sink.

“This is different,” I explained, attempting to collect samples without removing too much of my newly designated research habitat. “This is personal science. My face could be a biological hotspot of unprecedented diversity!”

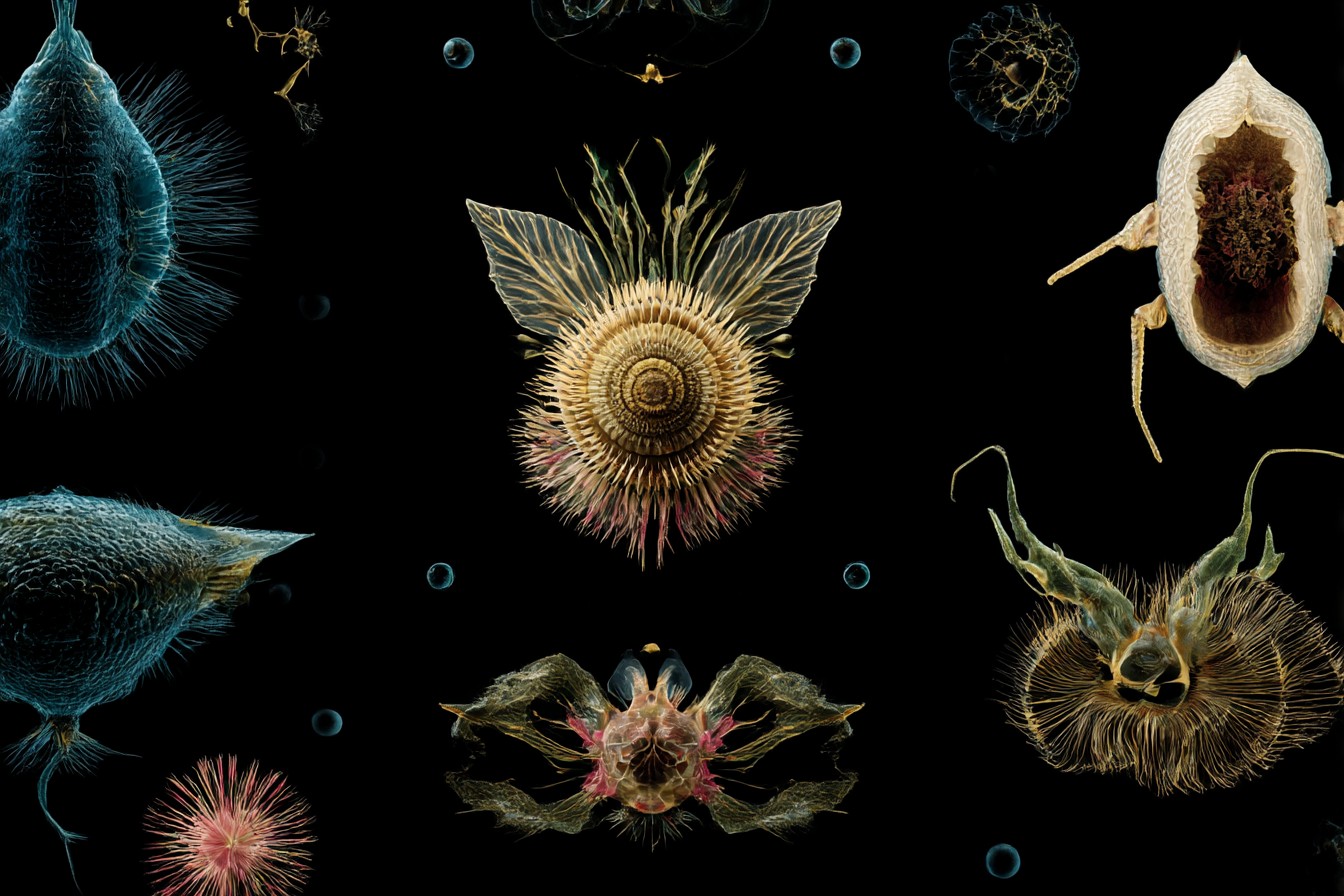

The initial survey was disappointingly straightforward. Standard microscopy revealed the expected Demodex mites, various bacteria, and the occasional food particle (note to self: napkins exist for a reason). But science is nothing if not persistent questioning, and I had access to considerably more sophisticated equipment at the lab.

So began what my graduate students now refer to as “The Great Facial Expedition of 2022.”

My methodology was simple—at least initially. I established a grid system dividing my beard into nine distinct zones: right cheek (upper, middle, lower), left cheek (same subdivisions), chin, and two sections along the jawline. Each zone would be sampled using sterile collection techniques, then analyzed through increasingly powerful microscopic examination, bacterial culturing, DNA sequencing, and whatever other methodologies I could sneak into the university lab after hours.

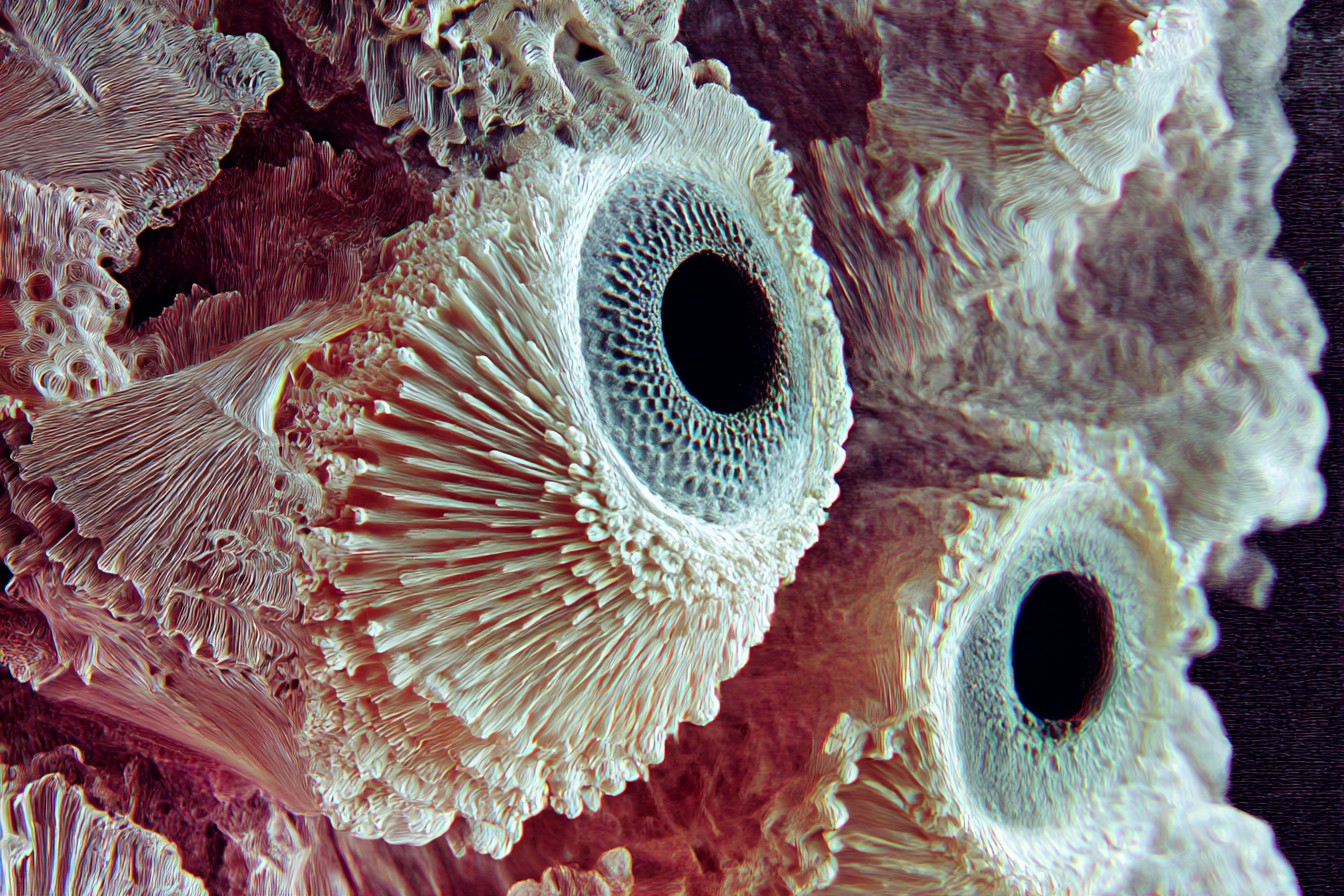

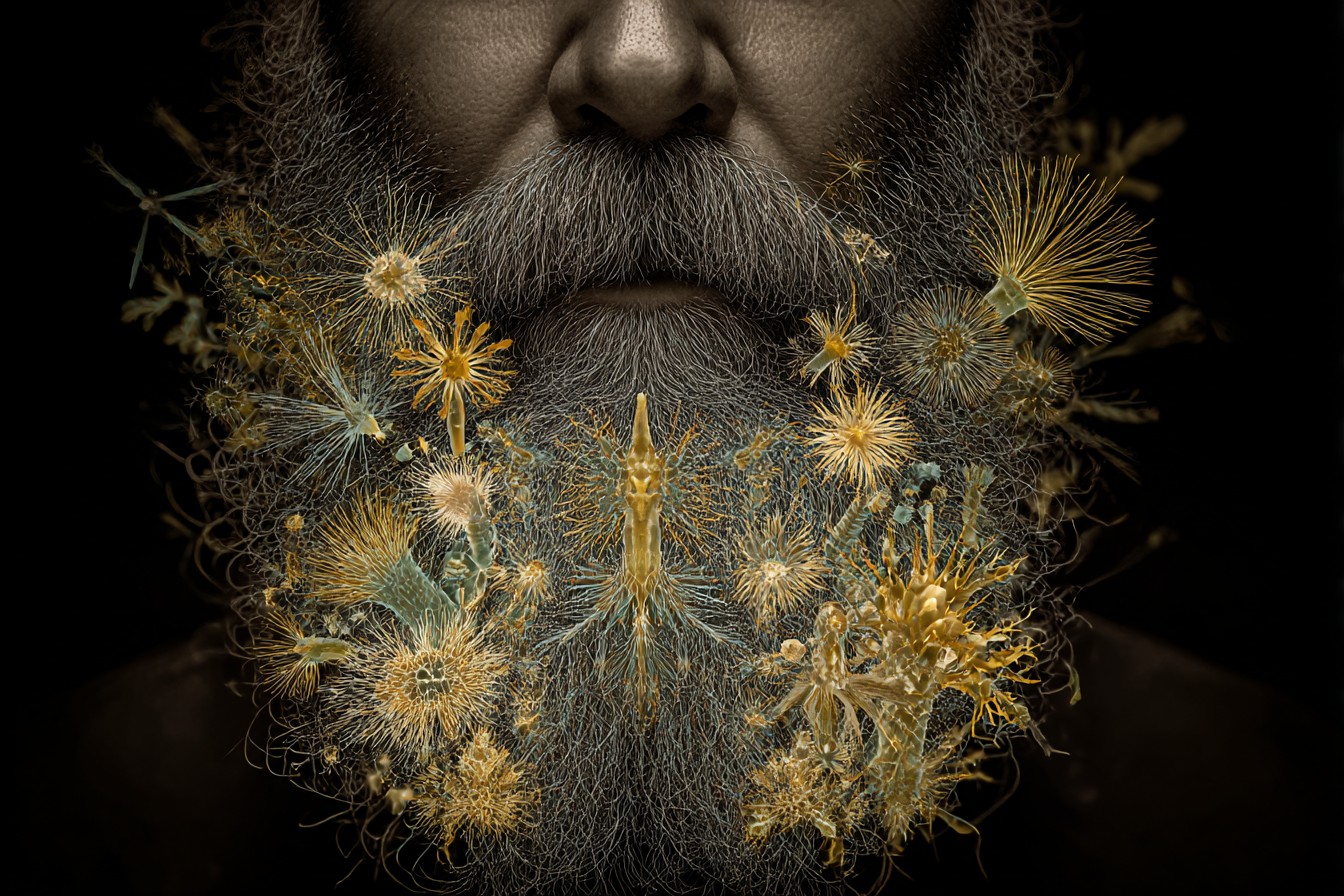

The first surprising discovery came three days into the investigation. The bacterial populations varied significantly between zones. My right cheek hosted primarily Staphylococcus epidermidis, while the left featured a remarkable diversity of Cutibacterium (formerly Propionibacterium) species. The chin region—the densest part of the beard—revealed something unexpected: stratification. Different microbes were living at different depths, creating what was essentially a microbial apartment building with distinct communities on each floor.

I documented everything meticulously. Temperature variations across facial regions (the area near my mouth was consistently 0.7°C warmer). Moisture levels (higher around the chin after drinking—obvious in retrospect, but now quantified!). Even the pH gradients that formed after eating different foods (spicy foods created measurable changes that persisted for approximately 37 minutes).

Dr. Khatri found me in the genomics lab at 2 AM, running samples through the sequencer.

“Please tell me those aren’t from a restricted pathogen,” she said, lingering by the doorway as if ready to trigger the containment protocols.

“They’re from my beard,” I replied, not looking up from the monitor.

There was a long pause. “Your… beard.”

“I’m conducting a biodiversity survey. The preliminary results suggest we’ve been underestimating facial hair as a microbiological habitat. Did you know there are elevation-dependent community structures? The outer follicles host entirely different bacterial phyla than the roots!”

Another pause. “Jamie, is this a funded project?”

“Self-funded,” I assured her. “Personal research initiative.”

“Right.” She nodded slowly. “Just… clean up when you’re done. And maybe seek professional help. Not microbiological help. The other kind.”

By week two, I’d identified seventeen distinct bacterial species, three fungal varieties, approximately five thousand individual Demodex mites (a surprisingly low population density compared to published averages—perhaps my face is inhospitable in ways I should be concerned about?), and various microscopic particles that originated from my apartment, office, and the burrito place across from campus.

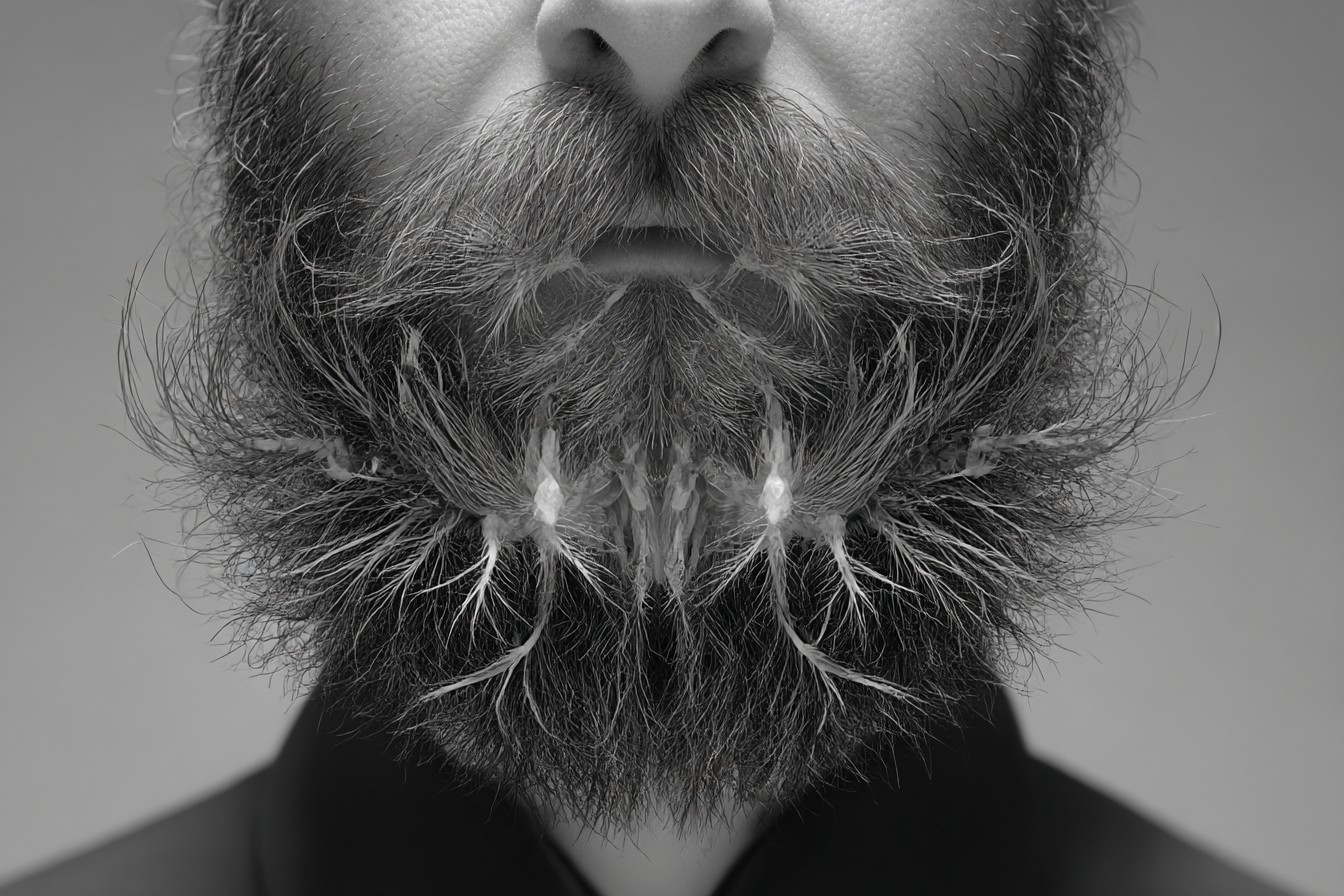

But the true breakthrough came when I began tracking movement. Using time-lapse microscopy on carefully extracted samples, I observed that the mite populations weren’t randomly distributed—they were forming territories. Specific colonies had established boundaries that rarely overlapped, suggesting some form of chemical signaling or resource partitioning. The bacterial communities showed similar patterns, with certain species clustering around follicles that produced specific sebum compositions.

I was witnessing microbial politics in real-time.

I became obsessed with documenting these societies. I stopped touching my face entirely. Scratching an itch could destroy weeks of established order! I developed a specialized feeding system, using a pipette to carefully deliver microscopic amounts of different nutrients to specific regions of my beard to observe how the communities responded. The left cheek populations flourished with olive oil introductions, while the chin dwellers showed remarkable adaptability to sugary substances.

“You’re feeding your beard?” Josh asked when he dropped by with dinner after I’d missed our weekly meet-up for the third time. “Intentionally?”

“I’m testing resource distribution dynamics in a vertically integrated microhabitat,” I corrected, carefully measuring sebum production rates with a modified oil-blotting paper technique.

“You look like a homeless wizard,” he observed. “A homeless wizard performing science on his own face.”

I couldn’t argue with his assessment. My beard had grown beyond the boundaries of reasonable facial hair and into the territory of what nineteenth-century alienists might have characterized as “morbid hirsute fixation.” Dark circles underlined my eyes from countless late nights documenting minute changes in my facial ecosystem. My skin was developing a pallid quality from the specialized facial cleanser I’d formulated—designed to remove dead skin cells while preserving microbial populations (a tricky balance that resulted in one particularly memorable chemical burn across my right jawline).

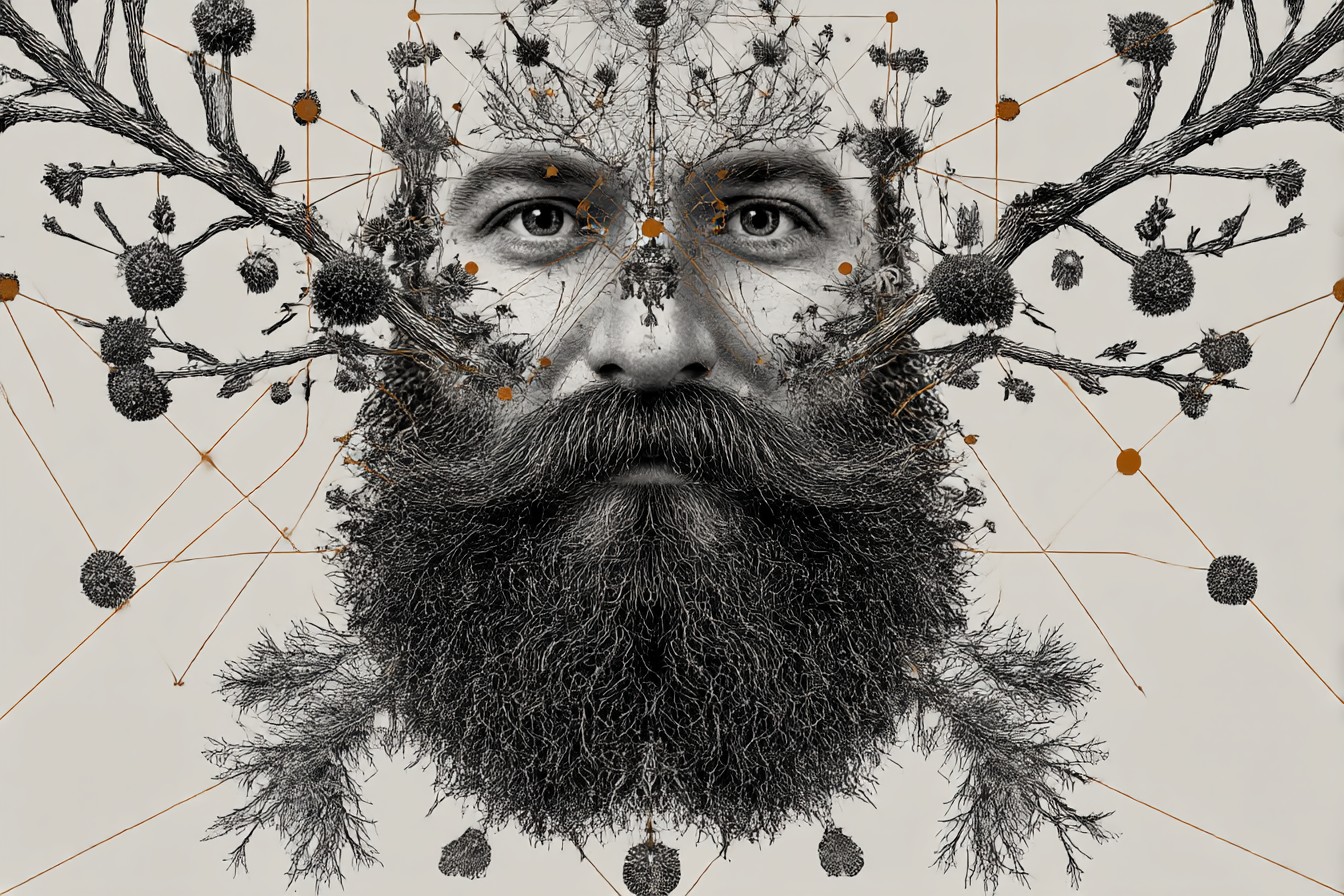

The ethical questions began troubling me around day twenty-four. Was I morally obligated to preserve this ecosystem I’d been studying? If I eventually shaved—committing what would effectively be genocide to thousands of organisms—would that be an act of scientific atrocity? These creatures had evolved to adapt specifically to my unique facial environment. Some of the bacterial strains I’d cultured showed distinct genetic variations from their commonly known relatives—they were becoming specialized to me.

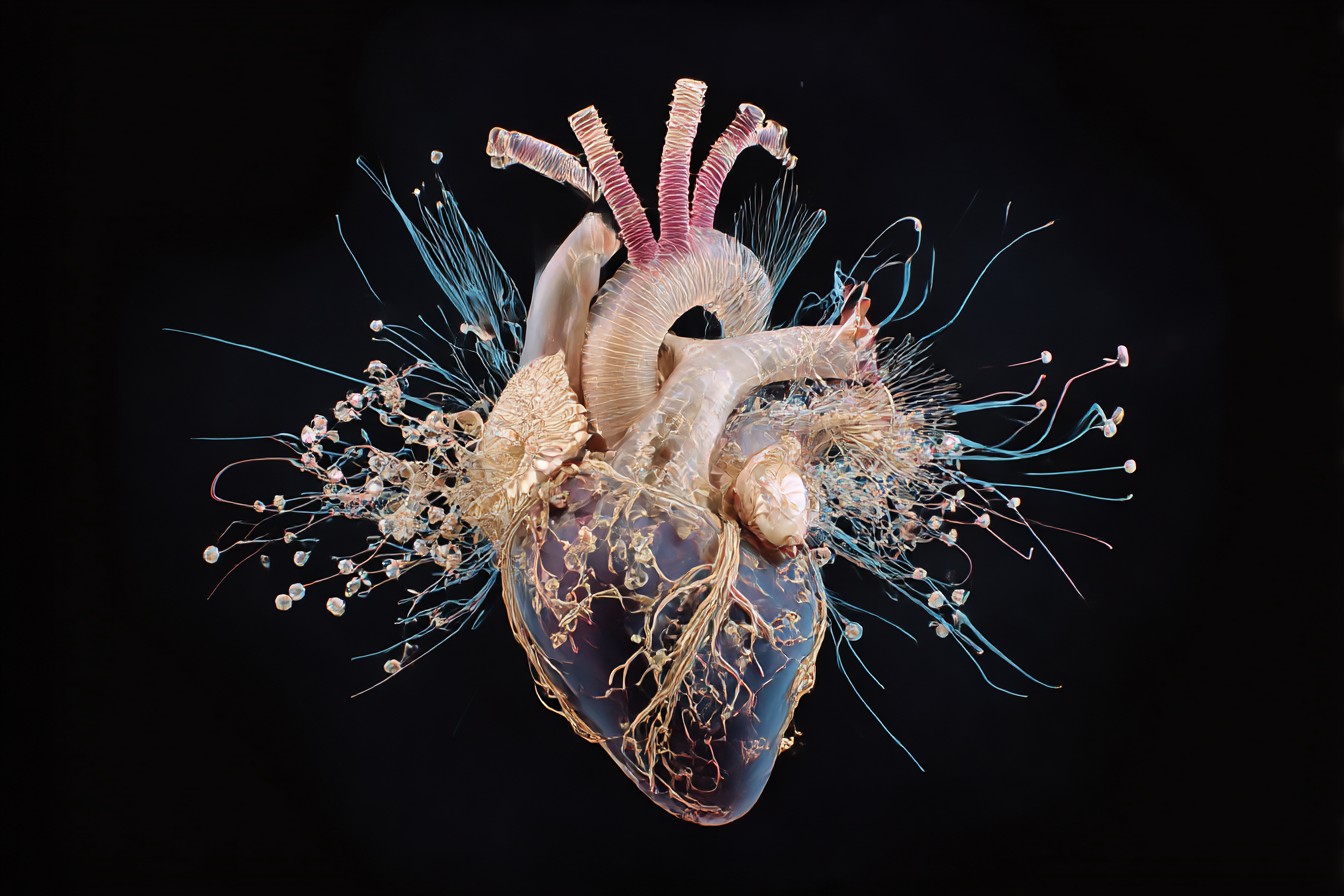

Had I become, in a very real biological sense, their planet?

This existential crisis coincided with a particularly awkward faculty dinner where the department chair pulled me aside to ask if my “situation” was related to a psychiatric evaluation I might need the university’s health plan to cover. I assured him it was purely scientific devotion, which somehow failed to reassure him.

The experiment reached its climax when I identified what I believe was interspecies cooperation. A particular strain of bacteria appeared to be producing compounds that specifically benefited a microscopic fungal colony, which in turn created an environment hostile to competing bacteria. They had formed a mutualistic relationship in the microclimate of my left jawline. I documented this with a fervor that Mei described as “concerning, even for you, and that’s saying something.”

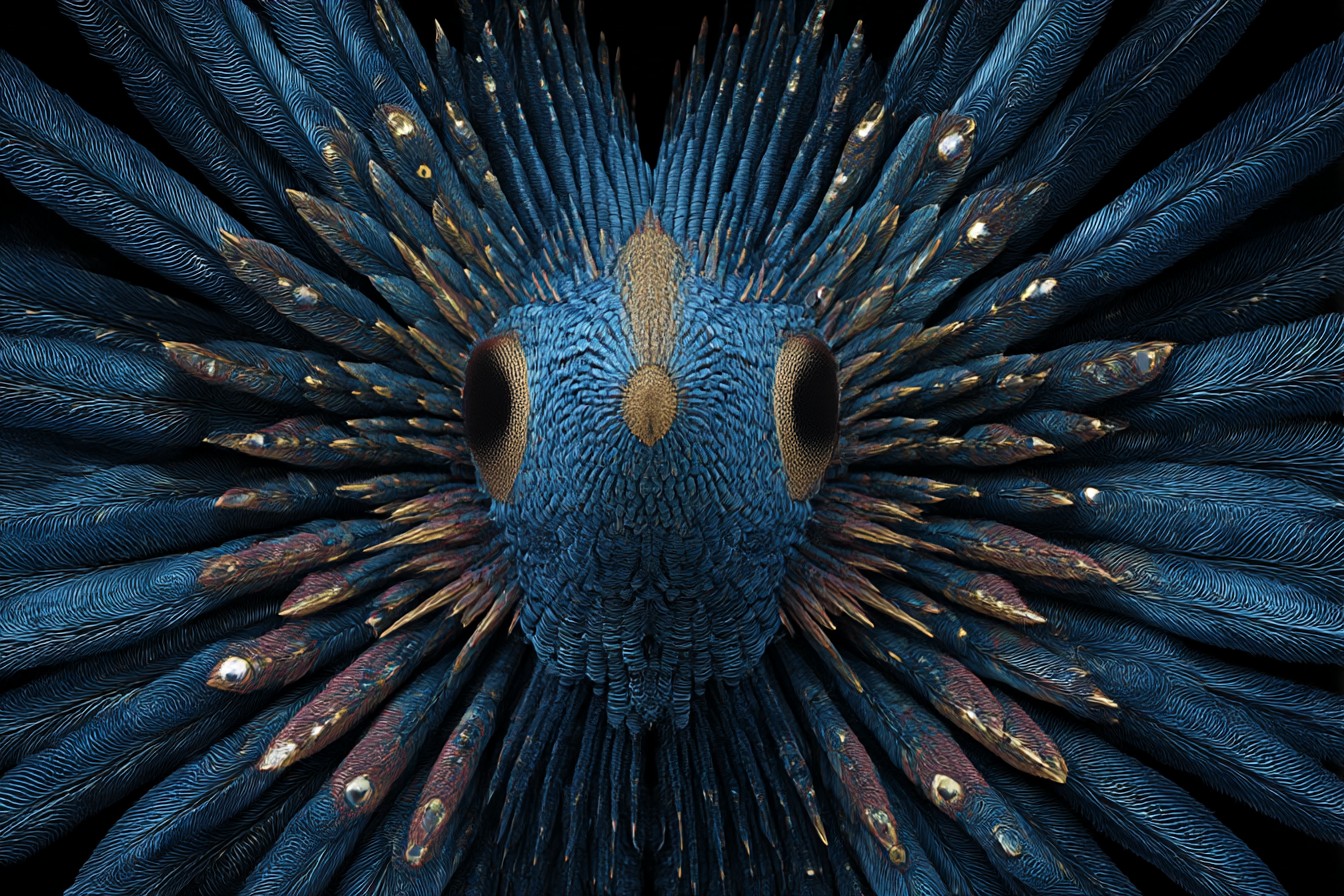

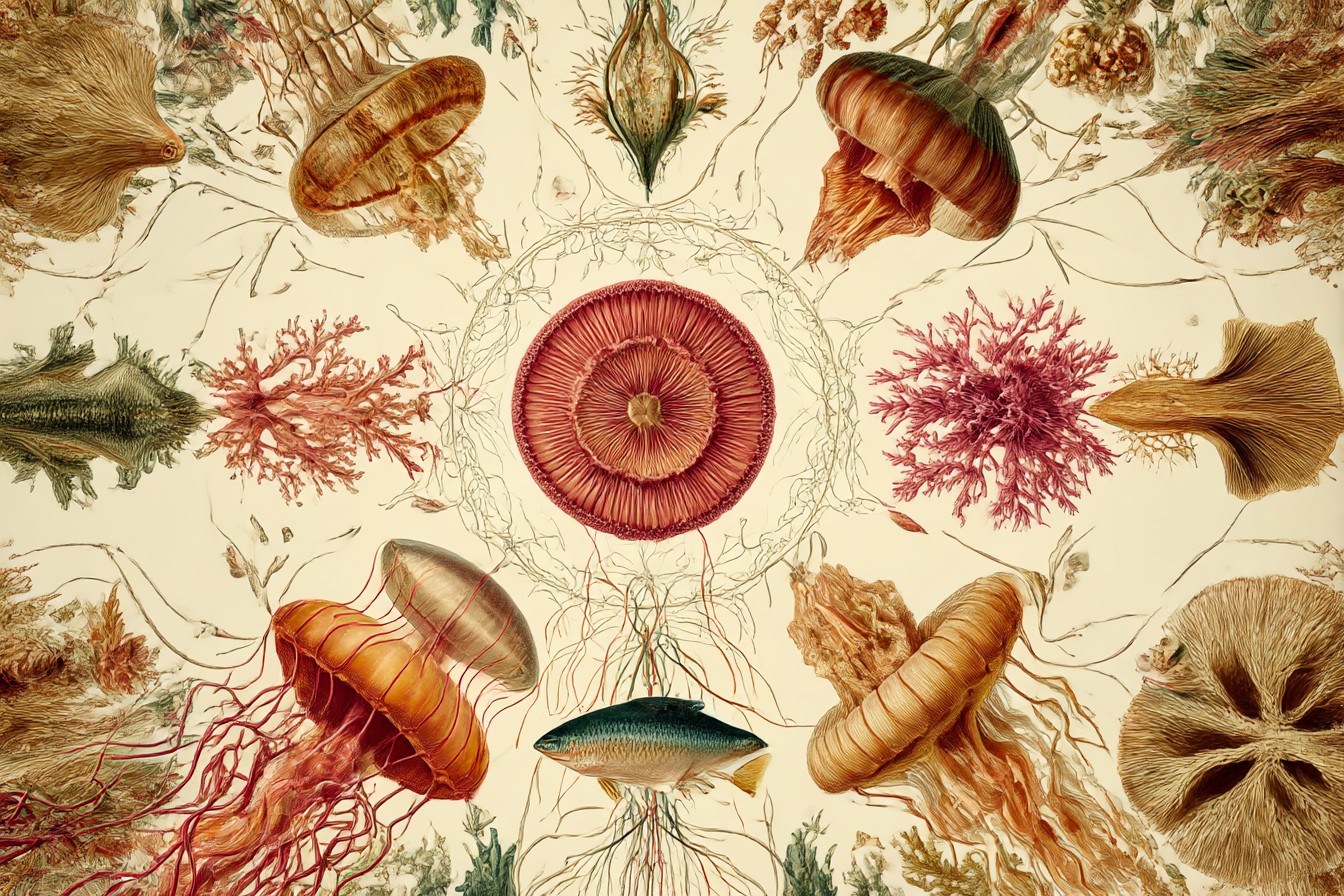

After forty-two days, I reached a conclusion that shook my understanding of human-microbe relationships: my beard wasn’t hosting an ecosystem—it had become an ecosystem that was hosting me. The organisms had adapted to my habits, feeding schedules, and even my emotional states (stress-induced hormonal changes created measurable shifts in microbial behavior). My face had become a planet, with weather patterns (perspiration events), geological features (skin topography), and evolutionary pressures that were shaping microbial adaptations in real-time.

The data revealed something profound: we are never truly individuals. We are communities, collectives, walking ecosystems with porous boundaries between “self” and “other.” My beard expedition had transformed from a quirky personal experiment into a philosophical inquiry into the nature of biological identity.

Eventually, societal pressure (and Mei’s ultimatum about kissing) led to the difficult decision to end the experiment. I documented the final state of the ecosystem with reverence, collected comprehensive samples for future study, and then—with genuine emotional conflict—shaved.

The massacre took less than ten minutes.

I’ve preserved cultures from the most interesting populations, maintaining them in the lab where we’re studying their unique adaptations. Several students have taken on projects investigating the specialized bacterial strains that evolved in the specific microenvironment of my facial hair. There’s even a pending publication on the topic (though the journal reviewers have requested I revise the methods section to sound “less disturbing”).

Sometimes I stroke my now-smooth chin and wonder about the civilizations that once thrived there—the complex interactions, the evolutionary innovations, the microbial dramas that played out across the landscape of my face. Their world is gone now, but the scientific insights remain.

And occasionally, when Mei is traveling for conferences, I find myself setting aside my razor. Just for a few days. Just long enough to wonder what new societies might be establishing themselves in the fertile territory of my follicles.

Because that’s the beautiful thing about science—and beards. Given enough time and the right conditions, whole new worlds will always emerge, ready to be discovered.