I always thought I had a pretty solid grasp on human creativity. The paintings in museums? Expressions of our aesthetic sensibilities. The symphonies that move us to tears? Manifestations of our emotional depth. The skyscrapers puncturing clouds? Triumphs of our problem-solving prowess.

Then I read Geoffrey Miller’s “The Mating Mind,” and everything went a bit… sideways.

It started as most of my intellectual rabbit holes do—with a seemingly innocent question that popped into my head while watching my friend Josh perform at an open mic night. His acoustic rendition of “Wonderwall” (god help us all) had attracted the attention of at least three women who kept making extended eye contact while he strummed away with unnecessary intensity. “Why,” I wondered, sipping my overpriced beer, “do we find musical ability so attractive when it has zero practical survival value?”

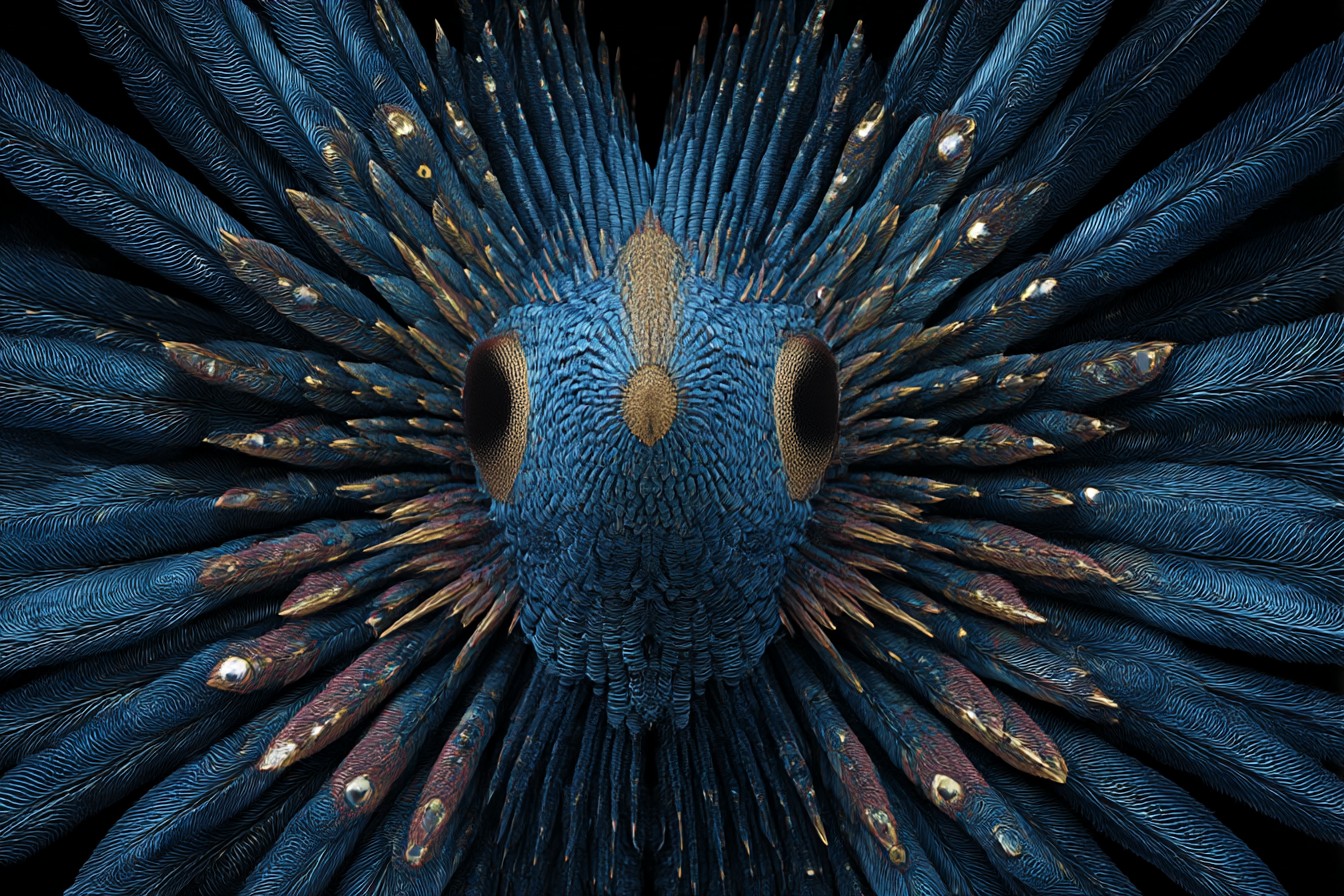

That question led me to evolutionary psychology, which led me to sexual selection theory, which led me to Miller’s book, which led to… well, me sitting in my apartment at 3 AM, surrounded by stacks of research papers, muttering “everything is a peacock’s tail” while Mei watched with increasing concern.

“Jamie,” she finally said, closing her laptop, “you haven’t blinked in approximately seven minutes. What exactly are you researching?”

I turned to her, wild-eyed. “Art is sex. Music is sex. Literature is sex. Architecture is sex. Philosophy is sex. Everything we think of as uniquely human achievement is actually an elaborate mating display designed to advertise genetic fitness!”

She stared at me for a long moment. “I’m getting you some water.”

Look, I’m not saying Miller’s theory explains everything about human creativity and culture. But the fundamental premise—that many of our seemingly impractical cultural behaviors evolved primarily as courtship displays—hit me with the force of experimental evidence I couldn’t unsee.

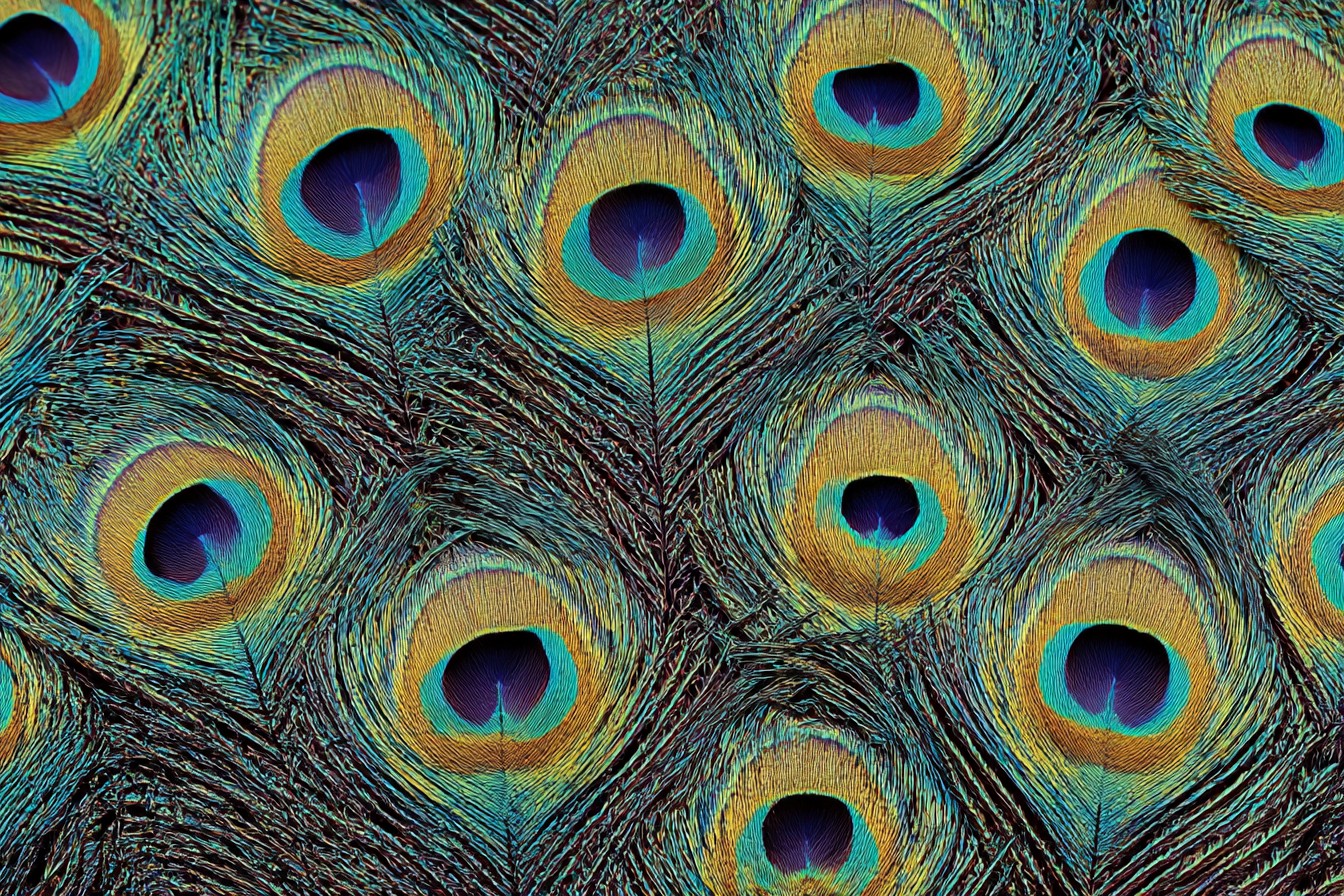

The theory goes something like this: Natural selection favors traits that help organisms survive and reproduce. But there’s this other evolutionary mechanism called sexual selection, where traits evolve because they’re attractive to potential mates, not because they help with survival. Think of peacocks’ tails—those massive, metabolically expensive, predator-attracting displays exist solely because peahens find them irresistible.

Miller suggests that human intelligence, creativity, humor, kindness, and moral virtues evolved through a similar process. These traits don’t necessarily help us survive better than other primates, but they do serve as excellent indicators of genetic fitness. They’re hard to fake, they require significant biological resources to produce, and they advertise our underlying genetic and neurological health.

I spent the next week conducting what Mei referred to as “increasingly disturbing observational experiments” at coffee shops, art galleries, and campus events. I created a makeshift ethogram to document human mating behaviors disguised as cultural participation. My field notes became increasingly manic:

Poetry reading, 7:30 PM: Male reader (approximately 28-32 years old) presented poem about existential angst using unnecessarily complex vocabulary. Observed pupil dilation in 4/7 female audience members during most linguistically complex stanza. Subject made eye contact with blonde in front row 17 times during 3-minute reading. Post-reading conversation initiated by blonde included touching of subject’s forearm 3x while discussing his “amazing imagery.”

Jazz quartet, 9:45 PM: Saxophone player (mid-30s) performed 7-minute solo with excessive technical flourishes. Detected increased attention from 6/13 potential mates in audience. Two individuals approached after performance. One offered to buy musician a drink. Control test: Asked drummer (similar age/appearance attributes but less conspicuous role) how many post-performance social approaches he typically receives. Response: “The saxophonist? Yeah, that guy gets all the numbers.”

My methodology was questionable at best, but the patterns became impossible to ignore. The novelist at the bookstore signing? Surrounded by admirers, predominantly of the opposite sex. The philosophy professor whose lecture on existentialism packed the hall? Receiving appreciative glances from students that had nothing to do with Sartre. The architect presenting his innovative sustainable housing design? Fielding dinner invitations alongside questions about load-bearing walls.

Things really went off the rails when I attended a prestigious science conference and suddenly couldn’t unsee the sexual selection dynamics playing out among my own species—I mean, profession. The competition for the most impressive presentation, the strategic name-dropping of publications, the subtle (and not-so-subtle) displays of intellectual prowess during Q&A sessions… it was peacocks all the way down.

“I think you’re overextending the theory,” Josh said when I called him at midnight to share my epiphany. “Not everything is about mating displays.”

“The evidence suggests otherwise,” I insisted, pacing my kitchen where I’d created a wall of sticky notes connecting various cultural phenomena to reproductive fitness signals. “Why do people train for marathons when we have cars? Why learn to play classical piano when Spotify exists? Why paint when cameras are superior at capturing images? These behaviors only make sense as fitness displays!”

“Maybe people just enjoy—”

“Enjoyment itself is an evolutionary adaptation to reward behaviors that increase reproductive success!” I interrupted, probably a bit too loudly for someone who had been awake for 30+ hours. “The pleasure we get from creating and appreciating art is nature’s way of making sure we engage in these fitness-signaling behaviors!”

There was a long pause. “Jamie, have you slept recently?”

I hadn’t. In fact, I’d spent the previous night conducting what I’d termed “The Beethoven-Bieber Experiment” at a local bar, where I alternated playing classical compositions and pop hits through my phone connected to the sound system (until the manager asked me to leave). My preliminary data suggested that while both musical styles elicited mating-relevant behaviors, the effects varied based on the demographic composition of the audience.

The real breakthrough came when I started applying the theory to my own life. All those science fair projects in high school? Desperate attempts to display my problem-solving intelligence to potential mates. My PhD dissertation? A 200-page peacock’s tail. The elaborate cooking experiments I subject Mei to every Sunday? Nutritional provisioning displays dressed up as culinary creativity.

“You realize,” Mei said one evening as I explained how her quantum computing work was really just an elaborate courtship ritual, “that if you reduce everything to mating displays, you’re creating an unfalsifiable theory? You can retrofit any human behavior to fit this framework.”

“That’s exactly what someone engaged in high-level abstract reasoning as a fitness display would say,” I replied, raising my eyebrows significantly.

She threw a pillow at me. “Your theory doesn’t explain why post-reproductive humans continue creating art, or why people create in complete solitude with no intention of sharing their work.”

Fair points. The data didn’t quite support a comprehensive reduction of all human creativity to mating efforts. But the framework still offered an explanatory lens that transformed how I viewed almost every human social gathering.

The university fundraiser where wealthy donors competed to announce the largest contributions? Status displays with reproductive payoffs. The neighborhood baking competition where Karen from three doors down presented an architecturally impossible soufflé? Demonstration of resource acquisition and processing abilities. My department’s publication celebration where everyone “casually” mentioned their upcoming research? Intellectual prowess signaling in its purest form.

I’ve had to dial back my enthusiasm somewhat after the incident at my cousin’s wedding. Apparently, the bride and groom didn’t appreciate my impromptu speech about how their vows represented “the culmination of a multi-year mutual fitness assessment process” or my observation that the groom’s heartfelt self-written vows were “a classic verbal fitness display demonstrating resource commitment potential and emotional stability.”

Look, I’m not saying that human achievement is only about mating. The most reasonable interpretation of the evidence suggests it’s more complex than that. Many of our creative and intellectual pursuits likely evolved initially through sexual selection but have been elaborated through cultural evolution and serve multiple adaptive and non-adaptive functions today.

But I will say this: Once you start seeing human culture through the lens of elaborate mating displays, it’s nearly impossible to unsee it. That guy at the coffee shop working on his screenplay? The woman at the gym performing unnecessarily complex yoga poses? Your colleague dropping casual references to their recent trip to Machu Picchu? All potentially engaged in sophisticated, evolutionarily-shaped courtship behaviors.

The preliminary results of my ongoing observational study (now in its third month, much to the concern of my friends and the irritation of several local business owners who have asked me to “please stop documenting customer interactions”) suggest that about 60% of public creative or intellectual behaviors show patterns consistent with mating displays.

The most surprising finding? I’m not exempt. As I was typing up my field notes last night, Mei peered over my shoulder and said, “You realize your obsession with this theory and all these elaborate experiments are themselves potential mating displays, right? You’re literally showing off your pattern-recognition abilities and theoretical innovation capacity.”

And well… the data supports her hypothesis. My own behaviors fit the pattern.

So here I am, still seeing peacock tails everywhere, still collecting observational data, still annoying my friends with evolutionary interpretations of their hobbies. Does this perspective explain everything about human creativity and culture? No. Is it a useful lens that reveals previously hidden patterns in human behavior? The evidence suggests yes.

Just remember: the next time you find yourself impressed by someone’s artistic talent, intellectual insights, or moral virtues, part of your brain might be running an unconscious subroutine that’s essentially whispering: “That’s some high-quality genetic material right there.”

And if you happen to see a scruffy scientist in a Cambridge coffee shop muttering about “fitness displays” while taking notes on patron interactions, please don’t interrupt my data collection. The research continues.

Leave a Reply